Crafting art from the skies: lessons in aerial photography

From Japan to the United States, fine art aerial photographer Donn Delson ascends up to 12,000 feet, capturing everything from sweeping cityscapes to whimsical patterns. This time, Nikon magazine flies with him

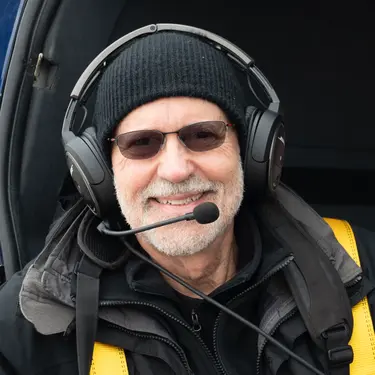

Donn Delson is suspended 2,000 feet above central London. With his legs perched on a doorless helicopter’s landing skid and strapped in with a yellow harness, the 75-year-old raises his viewfinder to his eye, rotates a dial, pauses and then captures the glistening lights of Piccadilly Circus. “Got it,” he says into his headset, after a quick glance at his Nikon D850 monitor. The pilot pulls away.

“I can’t help but be intrigued by perception and reality versus appearance,” the fine art aerial photographer says, his tethered camera body and AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8E ED VR lens in his lap as the pilot steers towards the Shard. “Many of my more whimsical pieces may not be what they seem from first glance,” he adds. As the helicopter hovers and tilts towards the tallest building in London, Donn raises his camera to his eye again. The shutter clicks. Unfazed by the sharp wind and vibrations, he is quick and precise. After not too long, the helicopter jolts south.

Getting started

So, how did Donn begin his journey? He spent many years photographing as a hobby, experimenting with landscapes, industrial laser light photography and long exposure. Then, in 2015, taking a helicopter to the top of New Zealand’s Remarkables mountains to see a glacier, the pilot casually asked if Donn wanted the door off so he could lean out with his camera.

“My wife said absolutely not, and I said yes,” he laughs. “The pilot put a harness on me, opened the door and that was the start of it.” His first thoughts? “Magnificent. That’s the only way to describe it – looking down with no encumbrances. I was hooked.”

Feathered. London. From the Points of View collection. D850 + AF-S NIKKOR 70-200mm f/2.8E FL ED VR. 90mm, 1/1250 sec, f/5.6, ISO 400 ©Donn Delson

Helicopter vs drone

Can you compare a drone to a helicopter? Donn doesn’t think so. “Drones don’t work for my style of photography as I need the visual connection of what I’m trying to photograph,” he says. “And I’m fascinated with measuring a space and visually moving through a space. Not to mention drones have flying restrictions, especially over urban areas. In a helicopter, I can up fly up to 12,000 feet and I’ve flown over molten lava!

“Drone photography is a fabulous way to get started and witness what the world looks from above, though. My top tip? Pick a trip and book a helicopter ride. I promise you’ll never look at your city in the same way again.”

Red Lock District. Amsterdam. From the Points of View collection. D850 + AF-S NIKKOR 70-200mm f/2.8E FL ED VR. 175mm, 1/1600 sec, f/5.0, ISO 400 ©Donn Delson

Best time to photograph

“The best time to fly depends on what you’re aiming to capture,” Donn explains. “If you want a ‘down image’ with little or no shadows, the best time to photograph is at high noon or on a cloudy or overcast day, which can provide a natural filter for reducing or eliminating shadows. Some photographs, however, look magnificent with the right shadows giving depth of field, and even changing the whole personality of the image. Twilight is a beautiful time to capture the magic of twinkling lights over a city.”

How to prepare before you fly

“Most of my images are found serendipitously,” Donn says. “I may have a general idea of an area where I want to photograph, but almost all my favourite images were accidental and gloriously unexpected sightings. I will use Google Earth cursorily before I fly to see if anything particularly draws my eye. However, trying to scan carefully over the many miles I tend to cover would take hours and be guaranteed to give me a headache!”

Watercolor. Dead Sea. From the Holy Land collection. D850 + AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8E ED VR. 24mm, 1/2000 sec, f/6.3, ISO 900 ©Donn Delson

Donn Delson on how to get tack-sharp shots in a helicopter

- Select AF-S

Use single-point focus in a helicopter as the subject is far away and not moving.

- 1/1600 shutter speed in the daytime

Although it’s possible to capture at slower speeds and you’ll have to at night, the reality is a helicopter has a lot of vibration and wind. If your objective is perfect clarity as mine is – especially as my prints can be upwards of 4x6m – it’s important to have a spectacular image that’s tack sharp.

- Photograph in burst mode

I use continuous high-speed burst mode as with the unsteady conditions produced by the helicopter it’s often the frames in the middle that are perfectly sharp. Last month I upgraded to the Nikon Z8 and I’m loving the 20fps burst speed.

- Always RAW

When you photograph in RAW, the camera doesn’t make any decisions, you do. You’ve got all the information that you can decide then what to do with.

- The most versatile focal length is 24-200mm

I’ll tweak my lens based on the height I’m flying, but I can almost always guarantee I’ll only need my AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8E ED VR and AF-S NIKKOR 70-200mm f/2.8E FL ED VR. As London has height restrictions due to the airports in close proximity, the AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8E ED VR was all I required. My D850 has always performed well in low light, especially at twilight. Now it’s time to use the Z8!

London Lights. From the Cityscapes collection. D850 + AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8E ED VR. 29mm, 1/50 sec, f/4.5, ISO 10000 ©Donn Delson

- Capture with a low ISO during the day

My preference is always lowest ISO possible to get the best image with the best colour data and the least graininess and noise, particularly for large-scale work and night shooting. It’s a real challenge to photograph at night in a helicopter and come away with images that will hold the detail and edges and not have too much noise when significantly enlarged. If you slow the shutter speed too much, you’ll have image blur; if you keep the shutter speed high to offset the vibration, you have to raise the ISO, sometimes dramatically, as is the case with the above image.

- Be aware of equipment weight

You need to be able to support your kit handheld as you can’t use a tripod due to the vibrations. You’ll also want to be careful not to lean your body against the door frame for support, as that will also increase your vibration.

Turntables. London. From the Points of View collection. D850 + AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8E ED VR. 52mm, 1/1600 sec, f/5.6, ISO 250 ©Donn Delson

- Capture with wide aperture

When photographing straight down (except for shadows), depth of field tends to be compressed so you can photograph wider open if you need to, based on available light. I’m always aware of a specific lens’ sweet spot for maximum tack sharpness across the image.

- Auto White Balance is all you need

I always leave my camera in Auto White Balance and adjust as necessary in Photoshop.

- Remove haze in post-production

In Photoshop, it’s generally easy to remove the haze and increase contrast and saturation.

Tree of Life. Dead Sea. From the Holy Land collection. D850 + AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8E ED VR, 24mm, 1/2000 sec, f/6.3, ISO 400 ©Donn Delson

How I got the shot

Tree of Life

“I was flying 5,000 feet over the Dead Sea and I spotted a ‘tree’ – it’s not a tree, of course, as nothing can survive due to the salt content, but it’s gullies that, from the air, look like roots of a tree getting sustenance from the sea. I called it the Tree of Life because the Dead Sea does give life – it provides an economy for all the communities that harvest its salt and create business for themselves.”

On the Green. Dead Sea. From the Holy Land collection. D850 + AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8E ED VR, 70mm, 1/2000 sec, f/6.3, ISO 360 ©Donn Delson

On the Green

“It struck me looking down at this little oasis in the Dead Sea that it looked like the ninth hole of a golf course I’d love to play. Instead, it’s actually a salt deposit. The story goes that a local person loaded the tree on a boat and placed it in the shallow waters there.”

Twinkle Twinkle LA 2. Los Angeles. From the Points of Light collection. D850 + AF-S NIKKOR 24-70mm f/2.8E ED VR, 70mm, 1/400 sec, f/2.8, ISO 2000 ©Donn Delson

Donn Delson’s top tips for aerial photography

- Training your eye is a combination of disciplined visual study while flying and looking for things that may represent something else at first glance. It’s a constant reminder not to make snap decisions about things or even people. It’s my own version of the painter’s trompe-l’oeil, where they paint pictures that are so realistic they look like photographs.

- Tell the helicopter company you would like to sit with the door off on the right side behind the pilot so the pilot can see exactly what you’re seeing and manoeuvre more effectively. You don’t need the opposite door off.

- Never enter or exit a helicopter from or towards the back as the tail rotor is a smaller, vertical propeller that is quite dangerous and seems invisible if it’s rotating.

- If you know your photo targets, speak with the pilot ahead of time to plan them and establish a communication process so they can respond to your requests.

- Tether your camera bag and camera bodies to the helicopter. As untethered objects may be dropped or pulled outside injuring the helicopter or someone on the ground, nothing can be loose in a doorless helicopter. You can use quickdraws that climbers use. They’re a combination of two carabiners and one sling that holds them together. I hook one to my camera strap and the other attached to a hook or wrapped back on itself around the metal bar behind the pilot.

- Unless the helicopter is hovering, never allow any part of your body or equipment to enter the slipstream outside your doorless seat. In other words, keep yourself completely inside the aircraft.

- If you plan to fly regularly, buy yourself a pair of noise-cancelling headphones (I prefer Bose). They’re terrific, have a Bluetooth connection, and you don’t have to share the mouthpiece with the last few dozen passengers. It dampens and almost eliminates the noise from the helicopter rotors and the wind. Plus, it enables you to communicate effectively and pleasantly with the pilot.

- With dry, high-pressure air, the temperature drops approximately 1°C for every 100m rise in altitude. That means at 1,000m the temperature will drop by approximately 10°C from what it is on the ground. Depending on the weather, it’s always smart to wear a couple of layers and a windbreaker. In cold conditions, I wear gloves with the shutter fingertip cut off, insulated clothing, wool socks and a beanie.

- Some helicopter operators require you to wear a harness, as opposed to an aviation seatbelt. While that increases the level of safety, make sure it’s always a quick-release harness, so that you can easily free yourself in case of an emergency that requires exiting the aircraft quickly. Always consult safety advice from your helicopter operator before you fly.

Keep up with Donn’s adventures here.

More in Travel & Landscape

Featured products

Unlock greater creativity